A question that always comes up, regardless of age, is how do I allocate my money once I start a savings program? The question soon morphs into how do I allocate my money after I have been saving for some time? I believe in simplicity. The combination of simplicity with mathematical elegance leads to a powerful solution that is within the grasp of most investors and most importantly, because it is comprehensible has a high likelihood of sustainability. This simply means that if you design a savings plan that is too complex, I doubt it will work. You can read A Rebalancing Tale for an example of a simple elegant solution. So when asked, how to allocate money at the start of a savings plan I always answer, the same way you would allocate money towards the middle or the end of a savings plan. This implies that selecting the initial allocation must be very important. It isn’t. As we learned in A Tale of Perspective, initially the most important thing is to start a savings program, regardless of how you allocate the money. However, your allocation takes on importance soon thereafter so it doesn’t hurt to give it some thought at the onset of a savings plan.

A question that always comes up, regardless of age, is how do I allocate my money once I start a savings program? The question soon morphs into how do I allocate my money after I have been saving for some time? I believe in simplicity. The combination of simplicity with mathematical elegance leads to a powerful solution that is within the grasp of most investors and most importantly, because it is comprehensible has a high likelihood of sustainability. This simply means that if you design a savings plan that is too complex, I doubt it will work. You can read A Rebalancing Tale for an example of a simple elegant solution. So when asked, how to allocate money at the start of a savings plan I always answer, the same way you would allocate money towards the middle or the end of a savings plan. This implies that selecting the initial allocation must be very important. It isn’t. As we learned in A Tale of Perspective, initially the most important thing is to start a savings program, regardless of how you allocate the money. However, your allocation takes on importance soon thereafter so it doesn’t hurt to give it some thought at the onset of a savings plan.

ASSET ALLOCATION AND DOLLAR COST AVERAGING

We have learned that asset allocation and dollar cost averaging are critical to building wealth. In fact they are the only two things required to build wealth. Bill Gates saved his money and invested it or allocated it into Microsoft stock. Warren Buffett saved his money and invested it or allocated it into multiple investments. Oprah Winfrey saved her money and invested it or allocated it in branding herself. If you look at anyone that has ever built wealth, of any magnitude, they have these two things in common. They saved money and invested it or allocated it. Which one is more important? Some would say that without dollar cost averaging you wouldn’t have to worry about asset allocation because you would never have money to allocate in the first place. But assuming that you have taken the leap and have decided to enter into an investment program, then asset allocation is more important than dollar cost averaging and it is easy to see why. Amongst the two titans, the first being dollar cost averaging or a consistent savings program and the second being asset allocation, the winner is asset allocation.

To understand how the logic works, we must first start with the standard dollar cost averaging model where a person invests a set amount of dollars into an investment program for a set period of time. In this case, let’s assume that the person invests $100/week for the foreseeable future.

In the above example this person invests $100 in the first week and it represents 100% of their total investment. In the second week they invest $100 and it represents 50% of their total investment. In the third week they invest $100 and it represents 33% of their total investment. In the fourth week they invest $100 and it represents 25% of their total investment. By the 100th week the $100 weekly investment represents just 1% of their total investment. I would suggest that by week 100, this person had better pay more attention to how they manage or allocate their previous 99 contributions than how they invest the 100th contribution. Thus is the case for asset allocation over dollar cost averaging. Both are necessary but one is clearly dominant. As a final tribute to the dominance of asset allocation, imagine the day where you stop contributing to your savings plan. At that point, we can call it retirement or once you have achieved a wealth objective, you no longer save money. At that point asset allocation represents 100% of the equation.

ASSET ALLOCATION VS DOLLAR COST AVERAGING

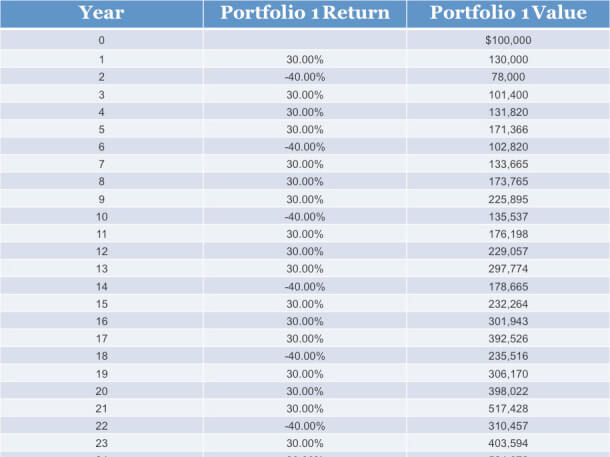

Since it’s obvious that asset allocation is more important than dollar cost averaging and becomes more important with each passing week, I think it would be a good thing to establish an appropriate asset allocation in the first week that one embarks on a savings program. You certainly need to have an asset allocation by week 100, why not in week 1? We know that over time equities outperform fixed income investments so it’s not unreasonable to assume someone that is trying to accumulate wealth would choose a very aggressive allocation to equities. But since this is a behavioral tale and we know that people will consistently make the wrong investment decisions let’s look at 4 different portfolios and see which one is the type of portfolio that someone that starts a dollar cost averaging program is most likely to follow. You can read A Portfolio Tale to see what I consider the type of portfolio that my experience tells me people can stick with through bull and bear markets.

HOW DO I ALLOCATE MY MONEY ONCE I START SAVING?

Since it’s my belief that the investor is an integral part of their portfolio I suggest that the best asset allocation is one that the investor can maintain. This means that it’s probably something less than 80% equities. I say this because I’ve observed the way investors behave and recognize that the probability of staying with an investment strategy increases as the volatility of a portfolio decreases. The corollary to this statement is that the probability of staying with an investment strategy increases as the rate of return increases. Simply put, there is a happy medium. Take a look at the following table to learn something about how you view a portfolio. If you were investing $100 per week into an investment program, which of the 4 portfolios would you most want to represent the results of your portfolio. In other words, which portfolio do you like better?

Which portfolio did you choose? On the surface you would choose portfolio 1 or 2 since after 21 months you ended up with the most money. However, not everyone does. They often choose portfolio 3 or 4. How can this be? We are all taught to maximize our wealth. Clearly portfolio 3 and 4 are inferior in that regard. Why do people gravitate to these two? There is a combination of behavioral terms for this but for purposes of this tale I like to call it “The Month 22 Effect.” People like to interpret past data and project it into the future and they like to examine past results and think they will repeat into the future. When they examine the 4 portfolios this is what they see.

When they look at portfolio 1 they see that it was worth $2,821 at one time and has been losing money recently. They don’t want to lose money in month 22 so they might avoid this portfolio. When they look at portfolio 2 they see that it lost almost 50% of the cumulative investment by month 16. They see that it’s been going up over the last 5 months but they still see potential danger. Most like it better than portfolio 1 because it has been going up recently but they don’t like the potential of a 50% loss in the horizon. Portfolio 3 got off to a slow start but has made more money than what was invested and shows good consistency and people reason that it will start going up soon. Portfolio 4 got off to a good start, lagged for a while then went up strongly. The beauty of portfolio 4 is that it is the only portfolio that every month has more money than the month before and has been making money at a good clip in the last few months. People will most often choose portfolios 3 and 4 over portfolios 1 and 2 despite the fact they didn’t maximize wealth.

This example in a nutshell is how people make asset allocation decisions at time zero or before they actually invest in or experience the results of one of the 4 portfolios. They project a certain level of behavior and think they will be able to maintain the portfolio they selected. However, these decisions go right out the window once they actually own one of the 4 portfolios and they start losing money. What they thought they could maintain they no longer maintain. They exit their strategy at typically just the wrong time. The wise investor recognizes their human tendencies. They recognize that they are an integral part of their portfolio and that the fear of losing money is greater than the exhilaration of making money. So, when confronted with reality they always prefer portfolio 3 and 4 followed by portfolios 1 and 2. In practice people don’t like the volatility of portfolios 1 and 2. They prefer something that gives them a smoother ride.

WHICH ASSET ALLOCATION IS BEST FOR ME?

Over the years I have presented my clients with this very same type of question to determine which asset allocation is best for them and to get a better understanding of their risk tolerance. I learn much from their answers and this is one of the main reasons that I can safely say that any advisor that manages a family’s money should incorporate a behavioral component into their portfolio composition. A behavioral portfolio that I think works can be read about in A Portfolio Tale.

For those that are curious, portfolio 3 has half the money invested in portfolio 1 and half the money invested in something that doesn’t pay any interest but doesn’t move up or down either; the equivalent of a money market fund that pays 0%. Portfolio 4 has half the money invested in portfolio 2 and half the money once again invested in something that doesn’t pay any interest but doesn’t move up or down either. This tells me that reducing the volatility or movement in a portfolio is very important to people. We started this tale by saying that the asset allocation should be set initially and this tale shows that in my opinion there is a strong behavioral case to be made for including safe investments in that allocation. Do it. Include safe investments in your asset allocation.

Growing up on the outskirts of Baltimore I was destined to be a Baltimore Orioles baseball fan. The bird was ever present. Later when I attended Johns Hopkins University the Blue Jay was our mascot and I became an avid lacrosse fan. With the Oriole and the Blue Jay I was getting a double dose of the bird. Later, when my wife and I purchase a home we bought a bird feeder and I am convinced that we are now the primary source of food, water and shelter for untold birds in our back yard. When developing this tale I wanted to pay homage to nature since so much of life’s cycles can be observed by just paying attention to what surrounds us. Please pay attention because I am about to explain the wealth cycle as I see it.

Growing up on the outskirts of Baltimore I was destined to be a Baltimore Orioles baseball fan. The bird was ever present. Later when I attended Johns Hopkins University the Blue Jay was our mascot and I became an avid lacrosse fan. With the Oriole and the Blue Jay I was getting a double dose of the bird. Later, when my wife and I purchase a home we bought a bird feeder and I am convinced that we are now the primary source of food, water and shelter for untold birds in our back yard. When developing this tale I wanted to pay homage to nature since so much of life’s cycles can be observed by just paying attention to what surrounds us. Please pay attention because I am about to explain the wealth cycle as I see it.

How can we easily remember the wealth cycle? I’m a big fan of using acronyms since I believe it’s the best way for people to remember things and thus I use the acronym BIRD. In A Wealthy Tale I define someone as wealthy if they can stop working and live indefinitely at their present standard of living by earning 4% or less per year return on their investments plus their guaranteed inflows from sources other than investments. In this tale I define what I call the 4 stages of the successful wealth cycle. If you are wealth challenged, meaning you can’t save money or have developed an expensive and unsustainable lifestyle, you need to change things so that you can get on the right track. What are the 4 stages? They are the Build, Income, Retain and Divest stages in a person’s life. Let me take you through the successful wealth cycle as I see it.

Assuming you are not born into wealth, the first stage of the wealth cycle is the wealth building stage. A person in this stage has only one objective and it’s to build wealth. When young and poor, a person has potential or human capital. They don’t have money so they must trade their skills for capital, which comes in the form of compensation or if you are self-employed through the process of profit generation plus asset appreciation. As a person ages if they save and invest or reinvest in their enterprise they gain capital or wealth while spending or diminish their human capital or potential due to the inevitable aging process. If a person successfully negotiates the wealth building stage of their life they reach what I call the Wealth Income Point, the WIP orWealth Inflection Point which I describe in An Absolute Tale. This is the point where a person examines the assets they have accumulated over their life and asks the question, can I generate enough income from my assets to never work again? It is an inflection point where the wealth builder has perhaps built sufficient wealth but they are not quite sure.

In differential calculus, an inflection point is a point on a curve at which the curve changes sign. the WIP or Wealth Inflection Pointis the stage in a person’s life where they sense a need to change from a wealth building strategy to something else. Most people don’t know what that something else should be but it’s their job as well as any good advisor’s job to recognize when a person reaches this stage and to advise accordingly. For an instructive tale about what happens when people reach the WIP I suggest you read An Absolute Tale.

The WIP is a very important stage in a person’s life and the area where most people come to first appreciate a good advisor. This isn’t to say that good advisors don’t work with clients that are in the wealth building stage of the cycle or aren’t appreciated by them. What it means is that when a person reaches the WIP I have seen that they start to look at their money in a different way. They take it more seriously than when they are younger and their portfolio is smaller. They want to understand how money works and they want to see how their portfolio stacks up for the future. If they’ve managed their own portfolio in the past they may hire someone since they often feel a need for professional guidance. It’s a critical stage because they sense that they may or may not be wealthy. They’re unsure of the future and their relationship with money and they look for a guiding hand. It is also the stage where a good advisor might first reduce the risk of the portfolio from a wealth building portfolio to a wealth income portfolio.

There are a number of decisions that must be made at the wealth income stage that aren’t required in the wealth building stage. In my opinion this stage is by far the most complicated stage of the wealth cycle in terms of planning since it has the most unknown variables. It is obviously less complicated than the wealth building stage where the only thing that matters is building wealth. What makes it so complicated is balancing the element of luck associated with forecasting what the markets will do in the next few years, short term for planning purposes, with the personal or life style objectives of the person. For a tale that shows how one couple handled the WIP read A Forecasting Tale. It’s a typical tale for people in this stage and will in one way or another apply to you when you reach this stage.

The wealth retention point in the wealth cycle is self-explanatory. You have passed the wealth building and the wealth income stages and you are clearly wealthy. Your goal at this point is to retain your wealth. One of my financial maxims is that financial planning can be summarized into six words; Get wealthy, stay wealthy, get wealthier. I have never examined a person’s financial situation where I didn’t focus on answering where the person was in relation to these 6 words. Correspondingly, I advised them to get wealthy, stay wealthy or get wealthier. Financial planning can’t get more basic than this and is why I think the single most important component to completing the wealth cycle successfully is superior investment performance. The rate of return on your portfolio matters and don’t ever get fooled into thinking it’s not important. Read A Martini Tale for a better understanding of what I mean by rate of return matters. Getting back to the wealth retention stage in the wealth cycle the last thing you ever want to do is to go backwards. This would violate the “Stay Wealthy” part of the equation. The Cuban saying would be “Never go back, not even to get a running start.” Staying wealth is serious business.

Though I have met many people that navigate through the wealth building, wealth income, wealth retention and wealth divestiture stages of the wealth cycle with very aggressive portfolios at the wealth retention stage if they ask my advice, I typically tell them to reduce their risk. I may increase portfolio risk again when they get to the wealth divestiture stage but if they are barely at the retention stage I believe risk reduction is prudent. I tell them this because by reducing the risk of their portfolio they reduce the probability of going backwards. I recognize that this is a personal preference but as an advisor it’s my responsibility to point out all the bad things that can happen when a person reaches for more when they already have enough. There is a reason why the saying enough is enough has stood the test of time. I have various tales about real people that have chosen to reach for more and instead found less. Don’t do it, it’s not worth it. Once you are wealthy you must retain your wealth.

The last stage in the wealth cycle is the wealth divestiture point. In this stage you are still wealthy, you can’t possibly outspend your assets, but you are no longer worried about yourself, but about your legacy. Since your financial needs will be met, at the wealth divestiture point you are more interested in what you will leave behind or divest when you are no longer with us. Please note that many people reach this stage at a very young age, so don’t fall into the trap of thinking chronologically about this stage. When a person reaches this point I often recommend they set aside sufficient funds to meet their needs in very conservative investments and then manage the remainder as though they are in the wealth-building stage of the wealth cycle. This typically means an increase in the risk of the portfolio from the previous wealth retention stage. This is counter-intuitive and would be financial heresy in the world of the typical and short-sighted financial planner that has some formulaic model that tells them to keep everything safe. My though has always been how safe do you need to be? If you can’t possibly outspend your money then take the part you never need to meet your financial needs and invest it as though you are wealth-building. Either your heirs or society will be better off for your efforts.

As an example of how to handle the wealth retention stage, I look at America’s premier investor, Warren Buffett. Mr. Buffett was not born rich and so he had to travel the wealth building road. If you examine his record you see that he spent about five minutes in the wealth income stage and went directly to the wealth retention stage. It is instructive to see what Mr. Buffett did once wealthy. He is reputed to have paid off his house, funded his children’s education, purchased and paid up in full a life insurance policy and set enough money aside to make sure his family would be reasonably secure. He then invested the approximately 98% of his remaining wealth as though he was still wealth building. He understood what the phrase “enough is enough” meant. He understood that once you are rich you stay rich but that you can do more for your loved ones, your charities and society by utilizing your talents. It’s a good thing that Mr. Buffett and others like him don’t listen to the short sighted and formulaic wisdom thrust on the typical investor that can’t possibly outspend their money. If they did, we would all be worse for it.

That’s the wealth cycle. If you remember the acronym BIRD you will probably remember that it stands for wealth building, income, retention and divestiture. You will also understand that each one of these stages calls for the individual to recognize at what stage they are in the cycle and adjust their portfolio’s risk accordingly. You should always know what stage of the cycle you are in. Lastly, always remember the magic 6 words; Get wealthy, stay wealthy, get wealthier.

If people were limited to understanding just one mathematical concept about money right at the top of the list would be the concept of compound interest. It’s essential that a person understand how compounding interest affect their ROI. If it were up to me it would be taught in every grade school from the time that children can perform simple percentages. This level of math is well within the level of most middle school students and once understood opens up endless possibilities for the imagination.

I remember how I was hooked. As a child in history class we were studying the tale of Peter Minuit and his purchase of Manhattan Island 400 years ago. As the tale goes he purchased this valuable real estate for $24. Since then there have been numerous sources that question the authenticity and validity of the purchase, but what struck me as curious was the concept of compounding and the idea that time was our greatest friend when it came to growing money. Our history teacher also happened to be our math teacher and he asked us a simple question. Did Peter Minuit overpay for his purchase of Manhattan? Of course everyone answered that he got the deal of a lifetime. Next the teacher asked us how we arrived at that conclusion. Soon thereafter he introduced the concept of compound interest and we all developed a different perspective.

It seems that the answer to our teacher’s question is that it depends on the interest rate that the seller were able to earn since the transaction took place. If we assume that the alleged $24 back then was worth what we consider to be $24 today and compounded it at 8% then the sellers got the better end of the deal. They would have taken that $24 and today it would be worth more money than all the value of all the world’s stock markets combined. This insight just knocked me off my feet. It also set in motion a series of insights that I use every day in my job as a financial advisor but those are for a later time. This tale is strictly about compounding.

THE CONCEPT OF COMPOUND INTEREST

This is A Compounding Tale that stars Mr. Stock and Mr. Bond. I chose the names because over time stocks will outperform bonds and is a theme that you will see throughout these tales. These two fellows were childhood friends, went to the same college, studied the same subjects and upon graduation at age 22 they each received graduation gifts in the exact amount of $1,000 from an anonymous donor. The anonymous donor had only one stipulation to the money he gave them. The stipulation was that the money had to be invested in either stocks or bonds and it couldn’t be touched until they reached age 65. To make things easier for purposes of this illustration, this $1,000 was placed in a tax-favored account that would compound tax-free until they reached age 65. Lastly, they were only given two investment choices. The first choice was a low cost stock mutual fund that was correlated to the general movements of the US stock market. The other choice was a low cost bond mutual fund that was correlated to the general movements of the US bond market. For those that don’t understand what correlated means in this case it means that if stocks made 10% per year for the next 43 years the stock mutual fund would also earn 10% per year for the period. Similarly, if bonds made 5% per year for the next 43 years the bond mutual fund would also earn 5% per year for the period.

As their name implies, Mr. Stock chose to invest his money in the stock mutual fund and Mr. Bond chose to invest his money in the bond mutual fund. Lets see what happens to their money over their lifetime. For purposes of this example we will assume that stocks returned 10% per year for the 43-year period and that bonds returned 5%. I chose these returns for the individual mutual funds because they are fair approximations of what I believe are the long term returns one can expect to achieve from stocks (10%) and bonds (5%). Though some may argue the finer details of my assumption, everything I’ve learned about the differences between stocks and bonds is that stocks return between 10-12% annually and bonds return between 3-5% annually over long periods of time.

What happens to the money of these two over time? 15 years into the tale, Mr. Stock’s portfolio is worth $4,177 and Mr. Bond’s portfolio is worth $2,079. In only 15 years Mr. Stock has a little bit more than twice as much money as Mr. Bond. By year 25 Mr. Stock’s portfolio is worth $10,835 and Mr. Bond’s portfolio is worth $3,386. Mr. Stock’s portfolio is now worth more than three times Mr. Bond’s portfolio.

By year 30 Mr. Stock’s portfolio is worth four times Mr. Bond’s portfolio. By year 35 Mr. Stock’s portfolio is worth more than five times Mr. Bond’s portfolio. By year 40 Mr. Stock’s portfolio is worth more than six times Mr. Bond’s portfolio. Finally, in year 43 when they both reach the age of 65 Mr. Stock’s portfolio is worth more than seven times Mr. Bond’s portfolio. Mr. Stock’s portfolio has grown to $60,240 and Mr. Bond’s portfolio has grown to $8,150.

The magic of compounding is that even though Mr. Stock was only earning twice as much return as Mr. Bond, 10% vs. 5%, Mr. Stock was accumulating money at a much faster rate than Mr. Bond because he was making more money on his money than Mr. Bond. Another way of thinking about it is that Mr. Stock made more interest on his interest than Mr. Bond did.

THE RATE OF RETURN TABLE

The table below shows actual numbers. Why the mathematical overkill in this tale? I believe that a complete understanding of this concept is crucial to any sound financial plan. I’ve met many financially successful people that don’t understand the magic of compounding. However, I believe they were able to overcome this deficiency. I don’t believe they succeeded because of their deficiency. As the saying goes, knowledge is power and a thorough understand of how money grows over time should be in everyone’s repertoire.

Rate Of Return Table

Results of $1,000 Invested

There are a few key observations to make from the table. The first and foremost is the cases of the 10% return as well as the 12.5% return. In both cases an investor made more money in the last 8 years, years 35 through 43, than they made from year 1 through 35. Though an investor would make a steady 10% per year in terms of return, they accumulate more money due to the fact that they earn interest on their interest over time.

The second key observation is that money does not grow in a linear fashion. If you look at the last column in the table it appears that money is growing at an increasing rate. Of course it isn’t growing at an increasing rate it is growing at a steady rate of 12.5%. However, in terms of absolute dollars, it is growing at an increasing rate—-this is the power of compounding over time.

I hope this tale conjures up more thoughts and questions on the topic of how money grows over time. In particular, I’d like to know why given such a simple concept and given such a relatively achievable threshold of 8% over time, which we learned from the sale of Manhattan, why everyone isn’t wealthy when they retire. Why can’t families transfer wealth successfully from one generation to the next? I would also like to know why given the knowledge that stocks outperform bonds over long periods of time why everyone doesn’t invest all of their money in stocks when they are building wealth. These questions and others will be answered throughout these tales.

This tale is not one that I’m particularly proud to tell. It teaches us the power of one extraordinary stock in a portfolio. For those that have seen the movie City Slickers and remember Curly famous line, “One Thing, Just One Thing” this tale is for you. In the movie Curly, played by Jack Palance, was explaining the secret to happiness. In this tale if there’s just one thing that you learn about individual stock investing it’s hold on to your winners.

This tale is not one that I’m particularly proud to tell. It teaches us the power of one extraordinary stock in a portfolio. For those that have seen the movie City Slickers and remember Curly famous line, “One Thing, Just One Thing” this tale is for you. In the movie Curly, played by Jack Palance, was explaining the secret to happiness. In this tale if there’s just one thing that you learn about individual stock investing it’s hold on to your winners.

The story starts out harmlessly enough. In mid 1990 I was asked to look into a company my friend was thinking about joining. The company was EMC. I liked it and bought shares for 22 of my clients and some for myself. A little over three years later I ended up selling the shares for 21 of the 22 clients that owned EMC including myself. At the time, I had made almost 15 times my money on this investment and the time to get out seemed appropriate especially since I had a few other companies that I thought offered better opportunities. Boy was I wrong. The real story is about Billy, the client that didn’t sell the shares.

It was just a matter of coincidence that I didn’t sell the EMC shares for Billy. At the time that I was contemplating selling it for all my clients, I had spoken with Billy and he told me about an unforeseen tax liability. He told me that if at all possible could I defer realizing capital gains until another year. I followed his wishes. I didn’t sell his shares of EMC. Billy’s original position in EMC had been about $5000 in mid 1990. By the time I sold it for everyone but Billy it was almost $75,000.

I kept an eye on EMC for the next several years and it moved up and down as stocks are known to do but as late as the fall of 1995 it was still worth roughly $75,000. The shares had not moved a lot during the almost 2 years since I had sold it for the group of 21 and myself. What happened next? The shares of EMC began to move up consistently. It didn’t take long for the stock to double and by Dec of 1997 Billy’s shares were worth about $600,000 and then they went up some more. To my regret, I sold some shares around this time thinking that the stock couldn’t continue to go up so rapidly and it represented a disproportionate percentage of Billy’s portfolio. By the end of 1999 the shares were worth almost $1.2 million dollars. EMC had probably been one of the top performers of the decade. I estimate that it had increased in value almost 500 times. This means that if someone had invested $10,000 at the start of the decade they would have almost $5,000,000 by the end of the decade. This is the power of one extraordinary stock.

What happened next? In early 2000 I sold half the shares in Billy’s portfolio when the shares of EMC reached 50% of his total portfolio. A few months later the shares had almost doubled in price again and I sold another half of what was left. As many of you know, the shares of EMC proceeded to drop by almost 95% from the peak price in 2000 to the trough price of 2002. I didn’t sell a single share of the EMC on the way down and still own it today.

What can we learn from this tale? We learn that some companies have the ability to generate extraordinary returns for their investors. This tale is closely linked to A Gardening Tale. In both we learn that selling individual stock winners is amongst the worst thing that you can do for your portfolio. We can also learn that luck plays a big factor in the investment process. Had Billy not spoken with me and explained his tax situation, I would have sold his shares along with all the others. Sometimes, it’s those tiny conversations that make a huge difference in a person’s results.

What else can we learn from this tale? We can learn that stock market success does not depend on picking stock market tops or bottoms. In the late 1990’s I sold shares for Billy as the price kept moving up and it became a disproportionate part of his portfolio. I didn’t sell his shares at the top of the market but I also didn’t sell them at the bottom of the market. Had I never sold one of Billy’s shares his original investment might have been worth as much as $5,000,000 at it’s peak and then when the stock of EMC went down 95% from it’s peak it would have dropped in value to about $250,000. It would have still been a great investment in hindsight to see $5,000 grow to $250,000 but by selling a little on the way up I was able to capture more wealth for Billy than by trying to pick a top like I did for myself and the other client’s that originally owned the stock.

Lastly, we can learn that if you are in the stock market long enough you come to realize that you can always do better. Many would go so far as to say that as a trader you are always wrong. You are not wrong in the traditional sense that you lose money. In fact you may very well have made a substantial amount of money. You are wrong in that in hindsight you can always analyze the subsequent market action of whatever it is that you are trading and come up with a set of what ifs that shows how you could have optimized your trade. As a trader you will always be subject to second-guessing and self-critique. I call this second-guessing the trader’s dilemma and illustrate it in A Trader’s Tale.

For as long as I remember I’ve been fascinated with the concept of wealth. I would consider individual wealth and collective wealth. I would wonder about wealth across borders and this lead me to think about wealth reallocation or redistribution within borders and across borders. Wealth creation also occupied my thoughts since I recognized that close to 99% of the world’s wealth had been created in the last 200-300 years. I would ask myself, why is wealth creation an exponential function, meaning that as a planet we are getting richer at a faster rate. I would ask the question, will this exponential growth continue. The point behind wealth is that it is much more of a theoretical concept than most people realize. Why does a middle class person in America have a standard of living comparable to the wealthiest titans of 100 years ago? Is it technological advance? Is it evolutionary? Is it how we organize our society? The answers to these questions will be ongoing throughout my life. But this tale deals with wealth at an individual level and is far more practical.

For as long as I remember I’ve been fascinated with the concept of wealth. I would consider individual wealth and collective wealth. I would wonder about wealth across borders and this lead me to think about wealth reallocation or redistribution within borders and across borders. Wealth creation also occupied my thoughts since I recognized that close to 99% of the world’s wealth had been created in the last 200-300 years. I would ask myself, why is wealth creation an exponential function, meaning that as a planet we are getting richer at a faster rate. I would ask the question, will this exponential growth continue. The point behind wealth is that it is much more of a theoretical concept than most people realize. Why does a middle class person in America have a standard of living comparable to the wealthiest titans of 100 years ago? Is it technological advance? Is it evolutionary? Is it how we organize our society? The answers to these questions will be ongoing throughout my life. But this tale deals with wealth at an individual level and is far more practical.

WHAT ACADEMICIANS BELIEVE

As a young man with no money and only armed with human capital or what others call potential, I studied the many ways that others built wealth. Along the way I invested 2 years of my life in what today I describe as a financial brainwashing that others call an MBA. The MBA is where the student gets their brain reprogrammed to think in a disciplined manner and accept academic financial and business theories as real world truths. The theories are based on unrealistic assumptions but worth studying as a mind expanding exercise since the real benefit is the resultant disciplined thinking. It had been pounded into my head that the only way to manage money was through the diversified portfolio and only the diversified portfolio.

Why do academicians believe so strongly in diversification? The answer is because academic studies prove that a person can’t outperform the stock market over extended periods of time once the portfolio is adjusted for risk. The catch is in the word risk and how academicians define it. What clever academicians do is say, yes that approach makes more money than the market but it is doing it in a riskier manner. They create a measure of risk which is inconsistent with how society defines risk. Society defines risk as not losing money. Academicians define risk by assuming people are equally happy going from poverty to wealth as they are going from wealth to poverty. Today, even the most hard-headed developers of these arcane academic theories recognize that this assumption is unrealistic. Unfortunately, the best minds have yet to develop an approach that explains the complexity of investing. We are thus stuck with what I call Newtonian Laws or Mechanical Laws in a Quantum world. This leaves the investor in a quandary. When the default portfolio is the diversified portfolio and there is no agreed upon reason to deviate, the investor chooses the default portfolio. For those that don’t know better or don’t want to know better or can’t figure out how to hire someone that knows better, I suggest you should have a diversified portfolio. However, you won’t get rich that way. I make this point very clear in A Tale of Diversification.

Towards the end of my education, I remember asking my favorite finance professor the best way to build wealth. So what did this wise professor tell me is the best way to build wealth? At the end of almost 2 years of study he said I should put all my eggs in one basket, preferably one that I knew and understood, and then to watch it carefully. He then told me that if I was lucky or skillful enough to build wealth then and only then should I look to manage my wealth by owning a diversified portfolio. He was clear to point out the stark difference between what he called the wealth building and wealth management stages of life. In the first stage you should take risks no longer required once wealthy. He went on to say that his advice wasn’t inconsistent with what he had preached for the last 2 years, his advice was adjusted for risk. I wouldn’t have understood the nuance of what he meant 2 years earlier but I did at that moment. At that moment of clarity, I also understood that my understanding wasn’t going to make it any easier to build personal wealth. In a connoisseur of the obvious fashion, my professor had advised me to do the same thing that others had advised for centuries and I also advise to those looking to build wealth. To build wealth you must focus or concentrate your resources and you must be very good at doing it.

SO WHAT IS WEALTH?

So what have I learned about the word wealth now that I am older. What is wealth? Some people define wealth as simply a person’s net worth. Some definitions are spiritual, others emotional and still others are anthropological, but since these definitions are outside my expertise I will focus on a financial definition of wealth. After years of dealing with people’s finances I am convinced that wealth is a state of mind but as a financial professional I can’t work with that definition. I need something concrete as do those that manage their own money. I need a formalized definition of wealth that I can apply when advising clients as does everyone else. I’ve come up with the following,

“You are wealthy if, at a 4% annual rate of return you could stop working and live indefinitely from the income your investments generate and guaranteed inflows from other sources while maintaining your standard of living.”

What can we gather from this definition? We can gather that wealth is not age, race, gender or nationality driven. You can be wealthy at any age or anywhere. What else can we gather from this definition? We can gather that wealth is relative based on the person’s lifestyle, assets, spending habits, background, geography, and investment performance. Lastly, we can gather that wealth can be attained in many ways and that if not properly understood and respected can be lost since it fluctuates daily.

The most complicated aspect of the word wealth and why I say wealth is a state of mind is that you can instantly go from being wealthy to not or vice versa simply on how you choose to live the rest of your life. If one day you for no reason other than “I want to” choose to increase consumption or up your lifestyle and you no longer fall under my static definition of wealth then presto—you are no longer wealthy. The reverse holds true as well. Wealth is thus an “in the present” phenomena that regardless of how much we may want to avoid it has a metaphysical side to it. How you look at wealth determines if you are wealthy or not. One of my friends when asked about wealth likes to say that the wealthiest person is not the one who has the most, but the one who needs the least.

Many fellow practitioners argue that my static definition of wealth puts too much emphasis on a person’s spending habits, consumption pattern or lifestyle. They argue that you can’t call a person with a net worth of $500,000 dollars wealthy while calling someone that has amassed a $10 million dollar net worth as not just because the one with more money spends too much. They argue correctly that the person with a $500,000 net worth can’t increase their spending habits, consumption pattern or lifestyle and is thus restricted and not wealthy. They don’t have the financial freedom or choice. Similarly they argue that the person with the $10 million dollar net worth can cut down on their expenses and easily meet our definition. I understand the classic argument that $10 million is more than $500,000 and that means they have more money. I recognize that my definition is limiting but for planning purposes one can’t just look at a person’s assets. Lifestyle is a crucial component and must be factored into the equation. Everyone’s heard of the athlete, businessman or entertainer that made a fortune to only lose it all due to a lavish lifestyle, poor investments, fraud or some combination of the 3. In an attempt to tie these two concepts together I believe that how much a person has, though a great indicator of whether they are wealthy or not by my definition, is not by itself sufficient to determine if they are wealthy.

To tie these two concepts together and thus add clarity to my definition of wealth I would like to introduce a term that is called the “burn rate.” What is the burn rate? It’s an old concept and one that most people will recognize. Most investors are familiar with the term burn rate as it applies to companies but it also applies to individuals. If a company is outspending what they take in by $10,000 per month and they have $100,000 in their checking account they have a burn rate of 10. This means they will be out of cash in 10 months. The same term can be used when analyzing a person’s finances. Many a time I have scribbled on a piece of paper a number such as 72 or 80 or 82 and hand it to a client. They look at it and ask what it means. I tell them “that’s how old you will be when you run out of money.” They get what I mean by burn rate very quickly when it’s illustrated so vividly.

My definition of wealth implies an infinite burn rate. This means that a person is wealthy if and only if at the current and projected spend rate they cannot exhaust their funds. Please note that investors must factor inflation into the spending equation. It is crucial but it is beyond this tale and you can read about it in An Inflationary Tale. This means that under our wealth definition once someone is wealthy you can’t determine if that someone is wealthier than another wealthy person since neither will run out of money. I suppose one could come up with a formula to show just how much wealthier a person is relative to another wealthy person but I don’t see the purpose.

This tale should be read after A Cyclical Tale. The reason I say this is because after reading this tale and A Cyclical Tale, you should be able to take a quiz which I call The Wealth Challenge. I present The Wealth Challenge in A Challenging Tale where I describe a few case studies of individuals and couples. The idea is to educate the reader on practical guidelines to what wealth means in practice. If they can correctly differentiate between, wealth or not, wealth challenged or not, they are far along towards their wealth quest.

This tale is a tale about financial or investment moderation. Much of Greek philosophy centers on what they call the golden mean. We see the first glimpses of this golden mean in the tale of Daedalus and Icarus. Daedalus built feathered wings for himself and his son so that they might escape their island imprisonment. Daedalus warns his son to “fly the middle course“, between the sea spray and the sun’s heat. Icarus did not heed his father; he flew up and up until the sun melted the wax off his wings. Socrates teaches that a man “must know how to choose the mean and avoid the extremes on either side, as far as possible”. Courage is a virtue, but if taken to excess would manifest as recklessness and if deficient as cowardice.

This tale is a tale about financial or investment moderation. Much of Greek philosophy centers on what they call the golden mean. We see the first glimpses of this golden mean in the tale of Daedalus and Icarus. Daedalus built feathered wings for himself and his son so that they might escape their island imprisonment. Daedalus warns his son to “fly the middle course“, between the sea spray and the sun’s heat. Icarus did not heed his father; he flew up and up until the sun melted the wax off his wings. Socrates teaches that a man “must know how to choose the mean and avoid the extremes on either side, as far as possible”. Courage is a virtue, but if taken to excess would manifest as recklessness and if deficient as cowardice.

Successful investing follows the golden mean. You must know the facts or you may fall victim to yourself at both extremes. Self-victimization or misperceptions come in two varieties, the first is unrealistic expectations and the second is diminished expectations. Neither one is good for your long-term financial health. You need to have realistic expectations and this only comes from knowing the facts and ranges of possibilities. You must have balance or moderation.

Understanding the history of returns is crucial so that you have some sense of how your portfolio is performing. However, as we learned in An Average Tale and A Volatile Tale, what is even more crucial in my opinion is to understand the variability of returns so that you know what to expect. If you don’t understand the variability of returns you can’t understand investing as far as I am concerned. It’s the equivalent of setting sail on a trip and not expecting a helping or hurting wind, rough or smooth seas. Every journey has its obstacles and the financial journey is no different. Understanding the financial obstacles provides you with a starting point to help avoid making irrational decisions that can hurt you.

Earlier I said that I have seen misperceptions work both ways. What does this mean in terms of investor behavior? It means I have seen clients stay with advisors that deliver little or no value while leaving advisors that do a fine job. It means I have seen investors adhere to a doomed investment philosophy while others abandon a proven strategy because it is temporarily out of favor. The problem is due to decision-making in a vacuum. They have no gauge, benchmark, measuring stick or understanding of what to expect from a portfolio. If they did they would know the facts and make informed decisions. You must have a way to measure what you are doing to succeed.

So why is this A Secret Tale? Because the person that inspired this tale told me to keep it a secret and for almost 20 years I have. This person was someone I met for a few minutes in early 1988, at his office, while I was cold calling and trying to build a clientele.

Back in 1988, I would make it a habit to solicit new clients in person before and after I would visit with current clients. I entered the lobby to his business, asked to speak with the owner if he or she was available and shortly thereafter Sam came out to meet me. He had my business card with him and came out and shook my hand vigorously. Since most people don’t welcome the sight of a solicitor, his behavior meant only one thing; he was already a client of my firm. He was meeting me just to see if something was up. Sure enough he was specifically the client of one of the top brokers in my office. After a few pleasant remarks on my part about how fortunate he was to work with such a talented broker I bid my farewell. As I started walking out the door, Sam called me back towards him. He met me half way and his face became very serious. He leaned over and in a hushed voice so that his receptionist wouldn’t hear said, “Let me tell you a little secret as to why I have kept my business with “Top Broker” for so long. I gave him $250,000 to invest in late 1974 when my father passed away and today it’s worth almost $400,000. I hope that one day you too can make your clients as much money as “Top Broker” has made me and I hope they can be as happy as I am.”

I was stunned. I’m pretty good with mental math and quickly calculated that the rate of return over the last 13 or 14 years on his original investment had to be somewhere in the neighborhood of 3 to 4% annually which was terrible. Late 1974 marked the end of a spectacular bear market and the start of a huge bull market rise in stocks. You would have had to try to only make 3-4% annually during this time frame. Sam’s portfolio had to be one of the worst performing portfolios in the city yet he had no idea. My curiosity was up, so I feigned surprise and asked if he had ever withdrawn any money from the account? He answered that he had not and that in fact he had started to make contributions of $500 per month over the last few years. I was even more surprised and went out the door congratulating him on how smart he was since I wasn’t going to discredit my firm, nor “Top Broker” with what seemed like a trivial matter such as the facts. As an aside, experiences such as this one contributed heavily towards my starting my own company a few years later. I felt a moral dilemma withholding the facts from Sam.

The subtitle of this tale is, “just the facts.” Some of you may recognize these words as those uttered by Joe Friday, a fictional character that plays a detective in the series Dragnet. The facts are very important when it comes to making sound decisions about your portfolio. Otherwise you can dupe yourself into thinking you are making a killing when you are not such as Sam.

Is this the end of this tale? Of course not, the reverse is also true and just as dangerous. You may think you are doing poorly while you may be doing very well. Perhaps you are the type of person that always thinks they can do better. If you think you are doing poorly or always want to do better then you may be tempted to take bigger and bigger risks. This behavior will ultimately lead to disaster. It’s important to know what to expect from your investments. You need to be realistic.

Let me give you a golfing example that happened to me that illustrates one of my blessings as well as shortcomings which is the need to do better. As many golfers know there are periods where they are playing particularly well. During one of these periods I had a lesson scheduled with my golf instructor. For those that have read An Expert Tale, my instructor was and is an expert. I had total confidence in his advice. At the time I was better than a scratch golfer and could on any given day, if things went my way, shoot under par at most any golf course. In other words, I was near the top of my game and my game was near the top of anyone’s game. We spoke for a while and he asked me what part of my game was bothering me the most. I answered that my driving was inconsistent. He gave me my greatest golf lesson that day as well as one of life’s great lessons. What did he do?

My teacher asked me to hit 14 drives, the number of drives one might typically hit in a real round of golf, and we would keep track of how far they went and how straight they went. After 14 drives we analyzed the results. I had hit it straight 9 times which means I would have been in the fairway and I had hit it slightly crooked the 5 other times. In addition, I had hit every drive more than 270 yards. My teacher asked me what I thought. I looked at him and said in a dejected voice looking for his complicity, “You see, I missed the fairway 5 times. All I want is to hit it 12 out of 14 times and when I miss I want to consistently miss it either left of the fairway or right of the fairway.” Ever the golf analyst, he then asked me if I was willing to reduce how far I hit the ball. I answered of course not. Then he looked me right in the eye and said “I can’t help you then, because what you are asking is to be the best driver of a golf ball that ever lived.”

I immediately understood his point and often apply this lesson to my everyday life. He was an expert on golf and could explain that I was seeking perfection or at least something that was unreasonable. I often think about Sam and my golf professional because they made a direct impact on how I view investment management and expectations. Know the facts. Know what you can accomplish. Be realistic about what you can and can’t achieve. It’s not a secret.

If you want to become an expert about what to expect from investments and their variability I suggest that you read Stocks for the Long Run, 4th Edition: The Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long Term Investment Strategies by Jeremy Siegel. If you want to learn about what I consider to be the important, a very condensed version of what I consider important, read A Statistical Tale.

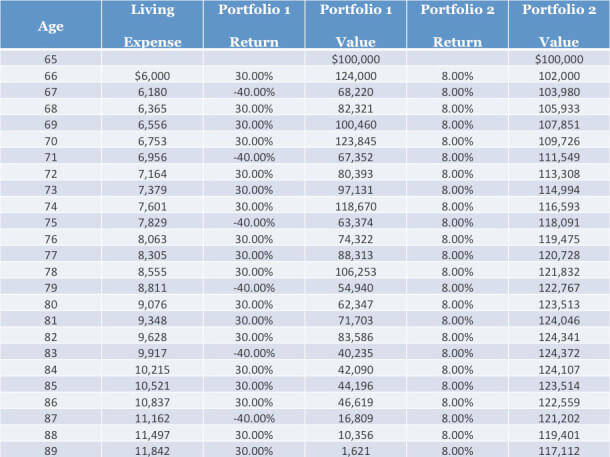

We’ve all heard the phrase “timing is everything.” It is especially important when you reach the stage in your life where your portfolio or assets must provide a stream of income for the rest of your life. This means that when you retire matters. If you retire a year earlier or a year later it can make a difference. There are plenty of phrases that speak to the word beginning. John F Kennedy’s phrase “Let us begin” is embedded in my subconscious as is the phrase “Well started is half finished” which I attribute to the Sisters of St. Joseph. So, when you begin and how you begin your retirement matters.

We’ve all heard the phrase “timing is everything.” It is especially important when you reach the stage in your life where your portfolio or assets must provide a stream of income for the rest of your life. This means that when you retire matters. If you retire a year earlier or a year later it can make a difference. There are plenty of phrases that speak to the word beginning. John F Kennedy’s phrase “Let us begin” is embedded in my subconscious as is the phrase “Well started is half finished” which I attribute to the Sisters of St. Joseph. So, when you begin and how you begin your retirement matters.

In the last tale, A Tricky Tale, I asked the reader to take a quiz. The quiz is at the end of the tale and immediately precedes this tale. It gives the reader a crystal ball that can see 25 years into the future and asks the retiree that must live off of the income generated from investments to choose between two mutual funds. The first mutual fund turns out to be the best performing mutual fund in the country for the 25 year period from 1969 to 1993. The second one is also a top-performing fund but far from number 1. The quiz is a trick question because the retiree will run out of money if they chose the best performing fund well before they reach the year 1993. They run out of money because the best performing fund made its returns in a very volatile manner. It had periods of spectacular returns as well as periods with substantial losses. In fact the top-performing fund from 1969 to 1993 lost 63.8% of its value during the June 1, 1972 through September 30, 1974 period. The second fund made steady returns and when it had losses they were much more contained.

The purpose of that tale was to illustrate the concept of the mathematics of recovery as well as the concept of volatility. The purpose of this tale is to illustrate the third lesson for retirees. It is the lesson of timing. Said differently, the investments you choose and the day you retire matters. The subtitle of this tale says that timing is almost everything. If you combine timing with the mathematics of recovery and volatility then you have everything for the retiree.

ANOTHER QUIZ

With this as background, let me give you another quiz. From A Tricky Tale, which would be the best investment for the new retiree if instead of retiring in 1969 they were to retire in 1970, 1971 or 1972 and choose between the two same funds over the next 25 years? Most people don’t want to be tricked again so they change their answer. They select the American Mutual Fund instead of Fidelity Magellan. If you changed your answer you once again answered incorrectly. The Fidelity Magellan fund is in fact a better investment if you retired in 1970, 1971 or 1972 even though you would have run out of money had you retired in 1969. The answer changes when you change the period. When you retire matters as well as how you choose to invest.

This is a short tale but it illustrates that from a planning perspective it is important to understand that a person that is working, saving and investing doesn’t have to worry as much about how his investments reach their destination nor when they start investing because time in is on their side and the mathematics of recovery doesn’t work against them. However, a person that has built capital and sees the end of their earning and saving years in the present or near future must think differently. It’s the same person but with two entirely different financial plans. Always know which person you are.

I have spent a disproportionate amount of my life over the two decades looking at financial websites and articles written by trained journalists posing as trained financial experts. One of my favorites is Yahoo! Finance and today I ran across an article with the heading “How Much Stock Should Older Investors Hold?” The writer interviews a number of financial planners and guess what they find? They find that fear is running throughout this “segment” of the population. I don’t mean to pick on the writer or Yahoo! Finance since an article like this is written on a daily basis in some reputed publication somewhere and has been written for the last 50 years and will be written for the next 50 years. But it is nonsense.

I have spent a disproportionate amount of my life over the two decades looking at financial websites and articles written by trained journalists posing as trained financial experts. One of my favorites is Yahoo! Finance and today I ran across an article with the heading “How Much Stock Should Older Investors Hold?” The writer interviews a number of financial planners and guess what they find? They find that fear is running throughout this “segment” of the population. I don’t mean to pick on the writer or Yahoo! Finance since an article like this is written on a daily basis in some reputed publication somewhere and has been written for the last 50 years and will be written for the next 50 years. But it is nonsense.

In summary the article tells us that older investors are holding less stock as a percent of their portfolio because they are fearful. They have been burned in the past and of course they fear the past will repeat itself. What I want to know is, are younger people not fearful? Does fear increase with age? What exactly defines someone as “old” when it comes to how much stock to include in their portfolio? Here is what I know for certain, attention –grabbing subjective headlines like these are meant to capture eyeballs but they are very destructive to the psyche of the untrained reader. The real question that should be asked is—How much stock should investors hold? Old or young has nothing to do with it. So, how much stock should investors hold? The answer is—as much as required to earn the returns necessary to achieve your goals and is why I call this tale A Required Rate Tale.

Subjective, attention-grabbing articles need to be closely examined. Articles that stress fear and encourage poor investment behavior are particularly dangerous because they encourage the reader to take an action or follow a “herd” instinct that may cause them to lower their allocation to stocks because “others” are fearful. These articles are tempting and offer the false hope of “safety” without the compromise of lower returns. Fear-based articles allude to the notion and encourage the reader to develop a mistaken belief that they can overcome the laws of simple mathematics. The lesson of this tale is the following—stop fooling yourself with thinking you can have your cake and eat it too. You can’t. You can’t earn stock market returns owning bonds and you can’t have the stability of bonds by owning stocks.

This of course brings us back to the question, how much stock should investors own? Once again the answer is whatever is required. So how much is required? That is the real question. This tale does not answer that question because it is a matter of your particular set of circumstances. But, it does frame the puzzle and it does tell you what is required based on two other factors, the inflation rate and the distribution rate. We learned about both of these factors in An Inflationary Tale and in A Distributive Tale. In summary those two tales teach us that the purpose of investing should be to at a minimum maintain your purchasing power and that in order to maintain purchasing power you need to make a higher rate of return on your investments than the inflation rate. So whenever you read headlines like the ones that play on fear and offer the false hope of reward without risk make sure you understand–it is a behavioral trap. Don’t fall for it. You can’t have your cake and eat it too.

Here is a surprise and something you won’t hear a journalist tell you given our societal tendency to think we are in control of our destiny. It really doesn’t matter what you as an older investor think, want, desire or perceive of the capital markets or the investment climate. When you retire and your money must work for you instead of you working for it, you run the risk of running out of money. The saying “You can run but you can’t hide” applies to your portfolio and the assets you select for inclusion in your portfolio. You can try to “run” from stocks or the perceived “risk” they pose but you can’t “hide” from the fact that bonds, money markets or CDs interest rates are not just currently low but historically don’t provide the solution for a perpetual flow of income into your retirement. So please understand that regardless of what you read or what others are doing, you are not immune to inflation or the amount of money you need in retirement or the allocation of stocks in your portfolio. Read this tale with the understanding that you cannot escape your mortality.

Since the intention of these tales has been and will always be to educate and promote financial literacy, this can only be classified as A Retirement Tale. However it has universal applicability. If you find yourself sitting on some board or institution or on top of a pool of assets you have to manage and protect, it also applies. This tale applies to anyone with a set amount of money they must grow in such a way as to achieve two goals. The first goal would be to provide a steady stream of income that keeps pace with inflation and the second goal is for it to last for an extended period. It doesn’t cover all of the factors in the decision-making process but it is the first step one must consider. Why is it the first step? Because it lets you easily see what the required rate of return must be on this pool of assets in order to achieve your goals. It is then easy to select the ranges of risk vs. return strategies you can target.

This tale covers 3 of the factors you must consider in order to make your money last. They are requiredrate of return, the inflation rate and the distribution rate. Of these three it is clear you can’t actively control the inflation rate. What about the other two? While in theory it is possible to control your distribution rate or the amount of money that your pool or portfolio must periodically distribute, in practice this just isn’t the case. You aren’t going to retire at age 65 or 70 expecting $50,000 a year from your portfolio and then magically only need $10,000 the next year. Once you set a distribution rate I have seen people that can alter it a little but in practice it stays constant and even needs to increase with the inflation rate to maintain a standard of living. So in practice, just like the inflation rate is beyond your control so is the distribution rate. This brings us to the last factor–-required rate of return. Guess what,required rate of return is also not under your control. The table that follows shows it is not under your control. If you require an X% rate of return to not run out of money then there is no way to dispute the math. What is under your control is the amount of stock you hold in your portfolio which is why I urge you to read An Asset Allocation Tale before proceeding.

This tale shows in unambiguous terms what the required rate of return you must earn on your portfolio so that it lasts for 30 years under different distribution and inflation rate combinations. You might even want to read the long and laborious paper I co-authored in the February 2010 Journal of Financial Planning article entitled A Simple Dynamic Strategy for Portfolios Taking Withdrawals: Using a 12-Month Simple Moving Average to understand the not so intuitive notion that allocations of 60%-70% of your money to stocks vs. bonds have historically given you a better chance of your money lasting 30 years than the opposite allocation. Lastly, the table assumes your annual distribution must keep pace with inflation—which is customary for analytical purposes. However, please recognize it is a heroic assumption in my opinion since most people I have met when they retire have no need to actually keep pace with inflation. They become what I call stealth savers.

Politically correct planners like to talk about designing portfolios where “you don’t outlive your assets” or “so you don’t exhaust your assets” but they are sugar coating things. This tale is important because what I and everyone I know worries about is the phrase “so you don’t die broke.” Once you understand the table you will be able to develop strategies to help you on your journey. If you read too many articles about what others are doing you might think you can escape your destiny but once again—-you can’t. I will provide you with some insights in A Preservation Tale to help you develop strategies to aid your journey.

When you look at the table you can see how difficult it is to have your money last for 30 years. 30 is the number many financial planners use as a goal for money to last. It was derived from the concept that a person retired at age 65 and then might live to 95 so one should plan for 30 years of portfolio distributions. Yet an examination of the table shows that in some cases even for people with the ideal low lifestyle requirements or low distribution rates and high rates of return on their portfolios they can run out of money before the Magic 30 is achieved. Said differently at least some part of your portfolio strategy is beyond your control. You simply must live in a country, society or time where the capital markets are conducive to your objectives.

Before reading any further please take a look at the table below. I consider it the first place a person reading a fear-inspiring article should look if they are determining how much stock they should hold. Remember fear-inspiring articles make people sell stocks. You must determine if it is a good idea. The table below will help you determine if your situation allows you to lower your allocation to stocks.

Let’s play a game called “Don’t Die Broke.” There are all sorts of ways to play the game but you must play wisely or you will lose. The way you start the game is to ask yourself the following question, how much money do I need on an annual basis in order to maintain the lifestyle to which I am accustomed? This always comes out to be a dollar amount and let’s say you answered $50,000 per year. The next step is to ask, how much money do I have? The answer is also always a dollar amount. Let’s say you answered $1,000,000. You then divide $50,000 by $1,000,000 to get a 5% distribution rate. You then look at the table and see the possibilities available to you.

What are the possibilities? You can see if the inflation rate is 0% you are required to make an annual rate of return of 3% per year for your money to last 30 years or more. But, if the inflation rate is 1% then you must make 4% per year. If the inflation rate is 2% you must make 5% per year. At 3% you must make 6% per year. At 4% you must make 7%, at 5% you must make 8%, at 6% you must make 9%, at 7% you must make 10% and at 8% you must exceed 10% per year.

It’s important for the reader to recognize that these numbers are the same for anyone regardless of how much money they have, where they live, what articles they read or what others are doing. This table is a universal table. Once you determine a distribution rate then there is a required rate of return associated with a given inflation rate. It is pure math and it is the same math for everyone. Once you determine a distribution rate the only thing that you can still control is your asset allocation which is why this tale is so intertwined with An Asset Allocation Tale. You cannot control the inflation rate.

How Many Years Will Your Money Last at Different

Distribution Rates, Inflation Rates and Rates of Return.

What’s obvious from this is that the higher the distribution rate and the inflation rate the higher the required rate of return. The higher the required rate of return the higher the risk a portfolio needs to take. The higher the risk a portfolio needs to take the higher the percentage of stocks a portfolio must hold. So the answer to the question How much stock should older investors hold is a function of their situation. However, there are some facts that are not preferences but subject to the laws of nature or mathematics. Do not delude yourself. Lastly, let’s recognize what we learned from A Distributive Talewhich is that the Distribution Rate is more important than the Inflation Rate when it comes to portfolio management so that you don’t die broke. This table is crucial to anyone that is embarking on the 30 year journey. It’s the road map. While a person can’t control the Inflation Rate they can control their lifestyle or Distribution Rate and they can control their portfolio allocation. Here is where the tradeoffs and conversations begin and portfolio management for this phase of life gets complicated and must factor other aspects into the equation. Let’s take some examples as how you might use this table.

Mr. and Mrs. Jones are 65 and have $1,000,000 when they walk into an advisor’s office and want their portfolio to last 30 years. They need $50,000 per year they tell the advisor. Let’s take a leap of faith and assume the advisor is a competent one. The first thing a competent advisor would do is to pull out the table above and make an assumption about a future inflation rate. Please recognize that your advisor is making a guess since neither they nor I nor anyone has a clue as to the accuracy of the forecast. Nevertheless since you can’t escape this need to forecast, let’s assume there will be an inflation rate of 3%. The advisor also recognizes that their services are not free so he or she adds their approximate 1% annual fee on top of the table calculation and determines The Jones’ must earn a 7% rate of return in order to not run out of money in 30 years. The advisor then informs them that the only way to earn this type of return is to take some risk with their portfolio. This means they must own stocks. He tells them there is no way they can earn 7% in a guaranteed account. If you refer to An Asset Allocation Tale I provide a chart that tells you approximately what level of risk as defined by how much money you need to allocate to the stock market in order to achieve a 7% rate of return. As we can see the historical average number is 40%. This becomes a guide because what we also see from the chart in An Asset Allocation Tale is if the Jones embark on a 7% targeted rate of return journey for the next 30 years and they start their trip at the wrong time they could lose as much as 26% in their first year. This would probably blow up their retirement plan, depending on the portfolio composition, due to the mathematics of recovery which we can learn about in A Tale of Recovery. Like I said earlier, there are tradeoffs and this is where conversations must begin when making decisions such as this.

The choices a competent planner might present is to lower the allocation from 40% stocks to some number that is more comfortable though based on averages less likely to succeed. Or perhaps convince the Jones to live on less than the $50,000 so that the required rate of return is lower which would then require a lower stock allocation. It could be a combination of the two and usually is in most cases. In many cases the solution might be to keep earning income for a few more years and not retire.

A final point about this tale is the other factors that need to be considered. The reality is that making money last for 30 years is a complex problem with no correct answers since a number of factors are beyond the investor’s control or the advisor’s control. I use the word complex not as a synonym for complicated. Complicated problems are deterministic and are solvable. Complex problems are not. If making money last for 30 years were an easy problem to solve, I and others would have solved it. However there are too many moving parts to the equation. The factors that matter are well known, they are the distribution rate, the inflation rate, the initial starting point or timing, the required rate of return and the volatility of the portfolio you choose. I urge the reader to also refer to A Tricky Tale so that they can see how portfolio timing and volatility play a factor in determining the appropriate strategy.

So is it a hopeless situation trying to make your money last? Must you have an uncomfortable allocation to stocks in your portfolio? The answer is as always—it depends. What I have seen in real practice is what I call The Just in Case Effect. This effect is characterized by the investor over-estimating the initial required distribution and then not increasing the distribution to keep up with inflation. Every table you will ever see such as the one I show above makes 2 heroic assumptions. The first is that the investor knows what their distribution rate should be. The second is that they want to keep up with the inflation rate. The reality is that people have a tendency to over-distribute from their portfolio and then save money from this over-distribution. This has two consequences. The first is that over time the investor starts accumulating cash that they either eventually re-invest in the portfolio or use it as a piggy bank so that they don’t have to take ever higher distributions to keep up with inflation. It is not unusual for investors that started out at age 65 for example receiving $3000 per month to still be receiving $3000 per month 5-10 years later. This self-imposed and stealth lowering of the distribution rate effectively means they are theoretically lowering their life-style and thus extending the time frame their money will last.

I have been unsuccessful trying to model this effect but recognize it is the way real people actually behave—-Just in Case. When making your plans you should recognize this is how you will also more than likely behave. This means that you can reduce your exposure to stocks if this is the way you will operate. By how much can you reduce it? It depends on your situation. I hope this tale helps.

Have you ever heard the expression, do as I say not as I do? I’m sure we all have. This expression typically roles off the tongue of someone that’s been there and done that. Typically these words come form a person that has accumulated great wisdom having been around the block a time or two. They are experts. It’s not a bad idea to listen to these people and take their advice. It’s important to understand their perspective before you do however. The reason I believe is because there is much to learn from how they came to these conclusions or wisdom. If you don’t know the why of the wisdom you quickly forget the advice. Learn the why.